She sat at the edge of a bar stool, tired eyes scanning the busy bar in Mokola, Ibadan, Oyo State, in South-West Nigeria. The sound of Afrobeats filled the air, and her half-filled glass of beer sat untouched.

“Abeg no mind my hair like this,” she chuckled, adjusting the wig without care. “I dey serve customers before you come. E just scatter anyhow.”

If looks are not deceiving, one would have taken her for just another bar attendant finishing her shift, a little tipsy, and plenty street smart. But the moment she opened the lid on her private life, it was clear: Ngozi***, who’s in her late 30s, has lived through chapters that many only scroll past on social media.

“I no dey form o,” she laughed. “This life, I don see am. Ehn!”

An aspiring designer with a National Diploma in Art and Design from The Polytechnic Ibadan, she was already ticking the right boxes to achieve her long-term dream of becoming one of the best designers in Nigeria. Still, it all came crashing down in 2011 when she had to drop out due to financial constraints. With bills piling up and no job, Ngozi was introduced into the dark world of digital sex trade, commonly referred to as ‘hookup’.

“I only wanted to do it for a few months to raise enough funds for further studies, but here I am 14 years later, and I’ve seen it all,” she said.

“No money to continue, no helper. Where I wan see school fees? Na so I stop. Certificate no dey cook soup!”

Ngozi found her first client on Facebook. However, she also sources clients through various ways.

Not every experience was good. She recalled how a particular man almost used her for a ritual. “One guy wey I meet for Facebook,” she said slowly, “na ritualist. I no know. Na God save me.”

Ngozi is bisexual. “I’ve been with both men and women. But I think I prefer women now. They understand pain better,” she said.

She alleged that even the police and soldiers are her customers. “There’s a club near Ring Road in Ibadan. Bad things happen there. Even police go there, and they know, they protect the place,” she added.

She still works at the bar in Mokola, in Ibadan. But her main means of survival is in the digital sex trade. It is dangerous and full of fear. “Some of us carry knives or screwdrivers in our bags,” she said. “Some girls go out and never come back. Some are drugged and die. Others just disappear.”

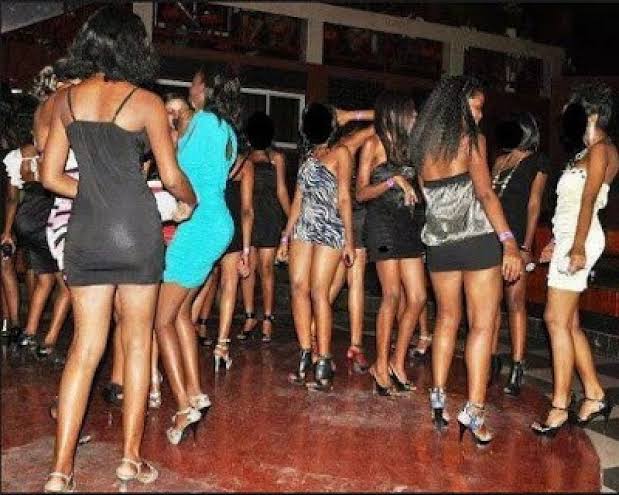

Ngozi’s story is not isolated. Across Nigeria, especially in urban centres, prostitution is booming, not as a trend, but as an economic lifeline for thousands of young women and men.

Far from traditional brothels, today’s sex trade is digital, run through encrypted chats, secret social media groups and coded statuses. Many young women, including students and jobless graduates, now turn to the digital sex trade, “hookups” for survival, masking transactional sex as a lifestyle.

When the world shut down during the COVID-19 pandemic, many people turned to all sorts of hustles to survive. But for one young man, Akin** in Ibadan, Oyo State, South-West Nigeria, survival meant turning to the shadows; pimping women to wealthy, pleasure-seeking men.

“It started during COVID,” he tells me casually, through a burner WhatsApp line. “The guys were stranded in Nigeria. Abroad guys. Lagos guys. They needed something. I gave it to them.”

He operates discreetly; no flashy social media accounts or Instagram stories. “Snapchat is for big girls,” he scoffs. “Me? I use WhatsApp. Coded things only.”

He refuses to disclose the number of women in his network, insisting on secrecy. But his business model is clear: he connects women, usually light-skinned, “clean” and sometimes chubby, to high-paying male clients, especially during party seasons and weekends when “big guys” flood Ibadan from Lagos or abroad.

“The big money comes during weekends,” he says. “If na special event, like wedding or naming ceremony, those dey pay extra. Especially if the client wants two-some or more, and guys wey dey on drugs, dem dey pay more too.”

He works alone, insisting that keeping the business small keeps it safe. “No crew. No wahala. I run everything by myself. Just me: Town Red.”

As for his cut? It’s a 40/60 split. He gets 40 per cent of the fee, but he’s quick to add, “If the babe nice, I fit no collect. Make she enjoy the full pay.”

On a busy weekend, he can rake in a sizable profit, though he refused to mention a specific monthly figure. “It depends. Some weekends, you go hammer. Some, not so much. But the real money dey when the big boys enter town.”

“It’s a business, lucrative, fast-moving and dangerously discreet. “It’s not about love or romance,” he says. “It’s survival.”

Michael Adeola* never planned to become a digital sex trade coordinator

Michael**, a well-paid professional based in Akure, Ondo State, South-West Nigeria, recalls a moment in 2018 that changed the course of his life. “I was walking through Alagbaka GRA and saw girls lining the street. That’s when the idea came to me: what if this could be safer? What if it could be more… organised?”

During the COVID-19 lockdown, his casual idea had transformed into a matchmaking network hosted on WhatsApp TV. At its peak, he managed over 500 members, with up to 10 hookup requests daily.

His system was not free; he charged ₦2,000 per connection and required ID verification. Despite his precautions, close calls haunted him, like the time a girl was caught in a client’s house by the man’s wife. He never met most of the girls in person, but the consequences loomed large.

“I drew the line at underage girls,” he said. But even that did not make the business right. By 2022, he shut it down. “I kept asking myself, if my daughter was in this, how would I feel?” he said. “That question haunted me.”

Yet, the market Michael exited did not die; it evolved.

An unregulated business where minors are also targets

Michael introduced me to a WhatsApp group still managed by an active pimp in Akure, Ondo State Capital. I joined “Match making!! (FG-1),” a group created in 2021, which still thrived as of July 18, 2025. It has over 500 members. No greetings. No guidelines. Just graphic videos, more than 30 daily, shared by the admin, showcasing nude women and explicit acts. I monitored the group for a month. Some days had more than 30 posts commodifying women, resembling a porn channel more than matchmaking. A connection fee of N5,000 was a criterion to get a client.

After each post, the admin followed up with a call to action: “DM, let’s talk price.” He messaged me directly, too: “Send your picture and location. Tell me what services you want.”

No age verification. No mention of consent. Just exploitation.

The deeper I explored, the darker it got.

In a group called ‘MATCH MAKING,’ created on May 13, 2025, with 339 members as of August 20, 2025, an advertisement targeting teenagers was posted. Despite including a caveat for those under 18, the admin, who has Oluwaseun on her WhatsApp, was identified by Truecaller as Chibese Ilado, shared a 30-second video of three minors, between 7 and 11 years old, making out. The video, made in 2022, was reposted by Chibese on her group. This violates Section 23 of the Cybercrimes Act, which prohibits the procurement, production, transmission, possession, and distribution of child pornography in any data storage device or computer system. These acts are offences punishable by imprisonment for up to 10 years or a fine of up to ₦20,000,000, or both.

Screenshot of the group Chibese’s group advertising minors who were making out

Using the child pornography video to promote her business, Chibese wrote, “Teenagers of nowadays self dey hot.” She also posted requests for “hook ups” and sex videos. Her action raised concerns about the protection of minors in such an unregulated platform.

Image of Chibese: Source: WhatsApp DP

To confirm if Chibese was indeed involved in the teenage sex trade, this reporter initiated a chat with her, requesting two teenagers aged 16. Chibese responded, “Ok, short time or overnight?” She further stated that a connection fee of ₦5,000 (about $3.30) would be required for each, adding, “Please send me a screenshot when you make payment.” She sent bank account details bearing a different name from the one Truecaller displayed.

Screenshot of my chat with Chibese

My next stop was Facebook. A search for terms like “hookup” and “Olosho” revealed a flood of public and private groups, here, here, and here. One group, with over 36,000 members, had a WhatsApp invitation link. I joined “ELITE CIRCLE GROUP,” where new members were welcomed and instructed to pay ₦1,000 monthly. On the surface, it appeared as a group of friends enjoying each other’s company.

When I messaged the admin that I wanted to join a hookup group, Elijah, aka “Dr. Lee,” clarified: “Not here. That’s a separate service.” Then came the real deal: “Send revealing pictures. I take 30% of what clients pay you. It all depends on how well you can take d**k.”

The admin turned out to be a man I later found out earned his first degree from the University of Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria, in 2007 and completed his master’s degree in 2010.

Again, no verification of age, no concern. Just commerce.

Michael had given me a list of the secret jargon:

Graphics of digital sex trade jargon

Soon, I noticed these terms on WhatsApp, Telegram statuses of pimps. Offers, services, and prices all wrapped in emojis and codes.

A screenshot of some of the requests on status

Behind the coded language and filters lies a bleak reality: this is not about pleasure. It’s about survival. Nigeria’s economic hardship is pushing a generation of women into a digital sex trade.

Take Amaka** (not her real name), a 24-year-old from Ibadan, Oyo State, Southwest, Nigeria. “I was broke,” she said bluntly. She started with whisper networks and soon learnt the codes: OL, HK, OS. From there, dating apps like the “Olosho App” offered her entry. Clients slid into her DMs. She shared pictures. They negotiated. They paid.

“The guys come into my DM,” she explains. “I send them my pictures, they ask for my price, and after we agree, they make full payment.”

Nigeria, with rising poverty and unemployment, sits squarely in the centre of this storm.

The National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) reported in 2022 that 133 million Nigerians live in multidimensional poverty. As of early 2024, over 106 million people live below $2.15 per day. The Q1 2024 unemployment rate stood at 5.3%, with women disproportionately affected at 6.2% unemployment compared to 4.3% for men.

Graphics of unemployment in Nigeria: By Juliet Buna

For Amaka, the statistics are not just numbers; they are her lived reality. Like Amaka, like Ngozi, many young women turned to the hookup world out of desperation, not glamour. But the price is costly: mental health struggles, identity crises, vulnerability to abuse, and above all, silence. Sometimes, that silence ends in death.

In 2024, Adebayo Olamide Azeez, a suspected ritual killer in Ogun State, confessed to murdering seven women he lured through a hookup app. According to police, he invited his victims to his residence in Atan-Ota under false pretences and killed them for money rituals. The Ogun State police spokesperson, Omolola Odutola, confirmed that at least 10 young women are reported missing daily, many linked to hookup-related activities.

The digital sex trade economy may seem like a survival strategy, but for many women like Amaka and Ngozi, it’s a path paved with trauma, exploitation, trafficking, and in some cases, death.

According to the National Agency for the Prohibition of Trafficking in Persons (NAPTIP), most of the individuals rescued from trafficking are women and girls, who are frequently exploited through sex trafficking, mostly with the promise of greener pastures.

Data culled from NAPTIP website: Graphics by Oluwadara Adepoju

These data reveal a worrisome trend: minors are among the victims of sex trafficking in West Africa.

But the physical dangers are only part of the story. When asked about younger girls in the sex trade, Amaka describes girls as young as 13 or 14 dressed in ways that mimic the influencers they see online. “It’s the culture,” she shrugs. “You watch celebrities online, the way they dance, dress, and act. It all promotes this lifestyle, even if it’s not intentional.”

Apart from being used to solicit girls, social media platforms are also used to get women to reveal their nudes for money. Coins for nudes are now common. On TikTok, young Nigerian women are being lured into exposing their bodies during TikTok live videos in exchange for virtual coins, coins that translate into very small cash payments. Known as the “Decimal Point” challenge, this trend is fueling concerns about digital exploitation and the growing intersection between social media and Nigeria’s “hookup culture.”

The trend, which has persisted for over a year, was flagged by X user @zuchminn on June 24, 2025. In the viral post, the user shared screen recordings of young women flashing their breasts, nicknamed “decimal points” by livestream hosts, on TikTok Live. These women were doing so at the instruction of male hosts, hoping to earn virtual gifts from anonymous viewers.

“This guy makes girls lift their tops in a flash to show their boobs for a few coins,” the post read, capturing just a glimpse of the growing trend.

Behind the Slang

The term “decimal point” is being used as coded language for a woman’s private parts. An investigation by this reporter traced the origin of the trend to at least two Nigerian TikTok accounts, both operated by male hosts who direct women to undress, dance, and follow sexual commands while livestreaming.

In several reviewed videos, male hosts, often off-camera, can be heard giving instructions such as:

“Remove your clothes.”

“Fling the cloth!”

“Raise your hands higher!”

“Shake your bum. Jump!”

Screenshots from the viral thread. The circled names in green are the masterminds behind the challenge.

The accounts were traced. One of the most active accounts is run by a user named Richard, whose TikTok handle is @obaviewonce_decimalpoin1, archived link (here), and display name is “RICHARD”. As of July 4, 2025, he had over 30,000 followers. Richard has publicly boasted about being suspended multiple times and returning with new usernames to continue streaming.

A screenshot of Richard’s page on TikTok

Another account, @specialpoint2, archived [here], with over 20,000 followers, follows a similar format. Both virtual hosts instruct young women to strip or dance sexually while encouraging viewers to “tap well,” a slang term for sending virtual gifts.

What’s even more concerning is that this explicit content appears to be gaining endorsement from popular figures. A search through the account reveals that the owner also runs a YouTube page. One video, archived link (here), reposted from a TikTok livestream and published on July 27, 2025, features well-known streamer and content creator Habeeb Hamzat, popularly known as Peller, actively encouraging participants to join @specialpoint2’s livestream, amplifying visibility for the platform’s activities.

A screenshot of Peller on the livestream of Special Point, one of the guys promoting the decimal point challenge

Efforts were made to obtain comments from Peller and his manager via Instagram and phone calls regarding whether the TikTok influencer is aware of the activities on the posts he promotes. However, there was no response as of the time of filing this report.

A screenshot of another account on TikTok

This trend is not just about breaking platform rules; it mirrors real-life sexual exploitation in a digital format. The male hosts act like online pimps or clients, giving commands to women who must undress or perform sexual acts in hopes of receiving gifts. The viewers, hidden behind their screens, act as paying customers, tipping in real time. Some of the livestreams are recorded and reposted across social media.

How It Works: TikTok’s Monetisation System

TikTok allows users aged 18 and above with at least 1,000 followers to host livestreams and receive virtual gifts from viewers. Viewers buy TikTok “coins” with real money and use them to send animated gifts like roses or pandas during live streams. Creators then convert these gifts into “diamonds,” which TikTok lets them exchange for cash.

However, the payout is minimal. For example, a rose gift costs one coin, about $0.014 (₦21). TikTok takes a significant cut (reportedly up to 50%), meaning the actual earnings for creators are meagre. Many of the women participating in the “Decimal Point” challenge end up earning less than one U.S. dollar per performance.

Violating TikTok’s Rules

TikTok’s Community Guidelines prohibit nudity, sexual content, and exploitation even for adults. The platform states:

“We do not allow nudity. This includes bare genitalia, buttocks, breasts of women and girls, and sheer clothing… We want to provide young people with a developmentally suitable experience. Content is ineligible for the ‘For You Feed’ if it shows body exposure of a young person that may present a risk of uninvited sexualization.”

Despite these rules, the Decimal Point challenge, as well as hookup culture, has managed to thrive, in part due to gaps in content moderation and enforcement, says Chioma Chukwuemeka, a digital safety advocate.

According to Chukwuemeka, digital literacy is the only sustainable solution, not censorship. “People are selling their souls for Mark Zuckerberg’s dollars, TikTok coins. But what they don’t realise is that the internet doesn’t forget,” she warned. “In five or ten years, you might want to rebrand, but your old, reckless content will still be there to haunt you.”

On the growing call to regulate social media, Chukwuemeka expressed scepticism, arguing that while regulation may seem like a quick fix, it could suppress the power of social media to give voice to the voiceless. “There are things we now know only because of social media. If it were just traditional media, those stories would have been gatekept. So, total regulation won’t work. What we need are strong laws and stronger enforcement. We are all content creators the moment we hit ‘post’. But we need to create responsibly. Social media has given us power; now we must use that power wisely.”

The Decimal Point trend is just one example of how social media is fueling a new wave of digital sex trade in Nigeria. While the content appears consensual, it raises serious ethical and legal questions, especially if any of the participants are minors or unaware that their videos are being recorded and shared.

A legal practitioner and human rights advocate, Barrister Deji Ajare, cautioned that digital sex trade in Nigeria, including activities such as advertising sexual services online, operating subscription-based adult content platforms, and running online escort agencies, could amount to criminal offences under multiple Nigerian laws, despite uneven enforcement.

Ajare pointed to the Cybercrimes (Prohibition, Prevention, etc.) Act, 2015, the Criminal Code Act (applicable in Southern Nigeria), the Penal Code (applicable in Northern Nigeria), and Sharia law (enforced in some Northern states) as legal frameworks that remain applicable.

Quoting Section 24(a) of the Cybercrimes Act, Ajare explained that: “Any person who knowingly or intentionally sends a message or other matter using computer systems or a network that is grossly offensive, pornographic, or of an indecent, obscene, or menacing character, or causes any such message or matter to be so sent, commits an offence.”

He added that the penalty upon conviction includes a fine of up to ₦7,000,000 or imprisonment for a term not exceeding three years, or both.

While acknowledging that Section 24 was amended in 2024 to address concerns raised in a judgment by the ECOWAS Court of Justice, which found that the original version of the section violated the right to freedom of expression under Article 9 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, Ajare said the amendment still retained punishments for sending content intended to “threaten, harass, or cause public disorder.”

He explained, “The amendment only narrowed the wording of Section 24 but did not remove liability for knowingly sending pornographic or fake content, especially when the intent is to harass or incite disorder.”

Ajare further cited the Criminal Code Act, emphasising Section 170, which states, “Any person who knowingly sends, or attempts to send, by post anything which encloses an indecent or obscene print, painting, photograph… or which has on it, or in it… any indecent, obscene, or grossly offensive words, marks, or designs is guilty of a misdemeanour,” adding that the penalty is one year imprisonment.

In Southern Nigeria, he noted, sections 223–225B of the Criminal Code criminalise activities related to prostitution such as soliciting, running brothels, or profiting from sex trade, with punishments of up to two years imprisonment.

“Although prostitution or sex trade itself is not expressly criminalised in Southern Nigeria, activities like operating a brothel or living off the earnings of prostitutes are prohibited,” he explained.

He also referenced the Penal Code applicable in Northern Nigeria, which criminalises solicitation, brothel-keeping, and procurement. More strictly, Ajare noted, some states governed by Sharia law expressly criminalise prostitution or sex trade in all forms, including the act itself.

“In Northern Nigeria, especially in Sharia-implementing states, prostitution or sex trade is criminalised outright. There’s little legal ambiguity there. What is criminal under the Criminal or Penal Codes offline can easily extend to online activity.”

Addressing the rise of digital sex trade, Ajare stated, “Advertising sexual services or escort offers via social media platforms like WhatsApp, Twitter, or dating apps may fall under grossly offensive or obscene communication as described in Section 24 of the Cybercrime Act — and likewise under the Criminal Code.”

He warned that even subscription-based adult content platforms like OnlyFans, when operated from Nigeria, could violate the law: “Anyone operating an OnlyFans page from Nigeria and distributing pornographic content over a computer network may be committing an offence under Section 24 of the Cybercrimes Act,” Ajare said.

Citing Section 34(1)(a) of the 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (as amended), which guarantees the right to dignity of the human person, Ajare remarked that while some may argue digital sex trade falls under personal liberty or expression, Nigerian law has not evolved to accommodate such practices explicitly.

“While there are constitutional rights such as freedom of expression under Section 39, and the dignity of the human person under these rights are not absolute. They are subject to laws made in the interest of public morality, Section 34, and order,” he explained.

Your Digital Footprints Leave a Bigger Trace Than You Think – ICT Expert Warns

Information and Communication Technology (ICT) expert, David Afolayan, raised the alarm over the hidden dangers of digital sex trade, describing it as a “multi-billion-dollar ecosystem powered by personal data.”

“Just registering on a dating or sex trade app means your actions are being tracked, stored, and monetised,” Afolayan said. “Your data is sold for targeted ads, and in serious cases, accessed by criminals or foreign actors. Once you opt in, you lose control.”

Platforms, he explained, make money through small user fees, but even more by selling user profiles to advertisers. “These apps are designed to keep you engaged and feed them more data. That’s where the real profit is.”

Graphics by Oluwadara Adepoju

Driven by her personal experience of overcoming childhood trauma and sexual abuse, the Founder and Executive Director of Blossom Girls Outreach Foundation, Doreen Omosele, addresses sex trafficking, including digital “sex trade” platforms and physical venues. “Some women engage in online and in-person prostitution to secure clients. We have reached out to over 500 prostitutes,” she explained.

Omosele emphasised the urgency of collective action. “Sex trade thrives where solutions are absent,” she said. “Government should adopt a well-structured approach combining rehabilitation, skill acquisition, and systemic support, noting that he foundation offers a replicable model to address this growing issue, while NGOs can implement it on the ground. Together, we can end this cycle and give women new beginnings.”

NAPTIP Responds

Reacting to the findings in this report, the National Agency for the Prohibition of Trafficking in Persons (NAPTIP) said that upon receipt of credible and actionable intelligence, the Cybercrime Response Team will immediately swing into action. “The N-CRT will conduct further covert investigation to uncover, gather, preserve, analyse, and report relevant evidence of the crime,” the Agency noted. “This will support the timely rescue of victims and lead to the apprehension and prosecution of the suspects involved.”

While acknowledging the complex and evolving nature of online exploitation, NAPTIP reiterated its resolve to remain proactive. “There’s no room for impunity,” the Agency concluded. “As long as we are provided with verifiable information, we will act swiftly and decisively.”

Note: Certain names have been replaced with pseudonyms, marked with an asterisk (*), to protect the identities of those involved.

This report was supported by the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism (WSCIJ) under its Report Women! Female Reporters Leadership Programme (FRLP).